I was going to move on to the subject of painting in this post. But I felt I should talk about another basic concept, Color Theory. The main reason I want to talk about it is because I’m surprised at the amount of people that have no idea, not only what a color wheel is, but what two colors mixed together make another color. So I’d like to touch base on this first before I move on. I’m pretty excited actually, this was one of my favorite things to learn in art class. So, who’s ready for a crash course?

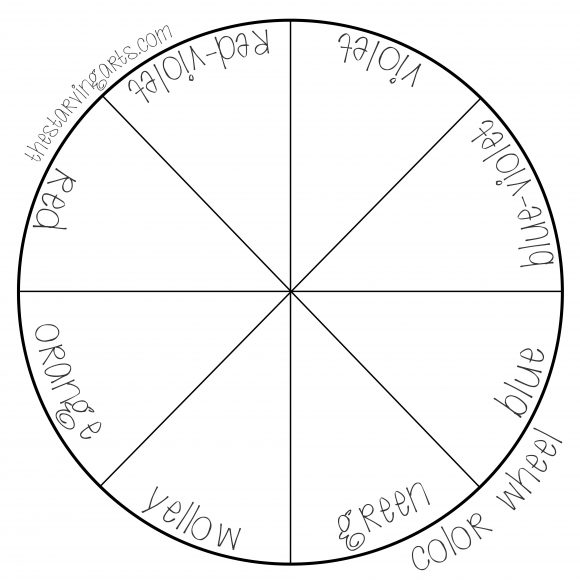

As you can see from the picture above, this is your basic color wheel. I’m going to focus on separate color categories at a time. But first, some vocabulary:

Hue: A fancy word for “color”.

Tint: Any color that has white added to it.

Shade: Any color that has black added to it.

Analogous: Any grouping of colors that are similar.

First up are the primary colors. Red, yellow, and blue. These 3 colors are important because these 3 mixed together can make up literally every other color of the rainbow. You cannot mix anything together to get these, they simply exist.

Next are the secondary colors. Orange, green, and purple. These 3 are from mixing the primary colors together.

Then there are the tertiary (or intermediate) colors. These are created when you mix the secondary and primary colors together.

Now you have a complete color wheel!

Except, there’s a little bit more to it than just a colorful wheel. Honestly though, if you only knew the above information, that’d be all you’d need to be an artist.

Well, at least to get started.

Most of the information I’m going to tell you is just a good thing to keep in mind when creating. It can really help make a picture outstanding and grab the audience’s attention. I’ve explained the main 3 color categories, excluding complimentary colors. Which, like I said, implemented properly, can really create some phenomenal art. And guess what? It’s really not even that complicated!

Complimentary colors are colors that are across from each other on the color wheel. Purple and yellow, blue and orange, red and green, etc.

Really, it’s that simple.

This is one of my complementary study paintings I did while in college. As you can see, it uses red and green.

On a side note, you should also know that when complementary colors are mixed together they create either gray or brown. Of course, this only works if the paints you’re mixing together are pure and don’t have other pigments in them. Which may not be noticeable to you, even if the tube just says “red” or “blue”.

I would like to also add another important aspect of using color. Which is simply knowing the difference between warm and cool colors.

Basically you split the color wheel in half.

Warm colors include: red-violet, red, red-orange, orange, yellow-orange, and yellow.

Cool colors include: purple (or violet), blue-violet, blue, blue-green, green, and yellow-green.

Here is a painting that I did implementing the warm and cool color scheme:

The cool colors are dark and deep, pulling you in. While the warm colors are not only bright, but pop out as well. Thus creating a sense of depth between the two.

I’ll go ahead and tell you that it’s a good idea to stick with a completely warm or cool color scheme while painting—at least when mixing your colors together. Otherwise, you might get some funky looking colors and you’re left wondering how yellow and red mixed together could make a mucky brown-grey color. (When you’ve actually unknowningly mixed together a yellow-green and an orangey-red.) It can be tricky sometimes, especially with the weird color names. You may not know just by looking at it.

And yes, I know this from personal experience.

Want to practice your colors? Here’s a few blank templates to mix colors! Use any medium you’d like.